Exploring Germany’s Berlin Wall History, 25 Years After The Fall

On May 23, 1962, a 14-year-old boy named Winfried Tews ran for dear life.

Scrambling over the walls and jumping into a canal, desperation propelled him forward.

Despite the dangerous situation, despite the people he was leaving behind, despite the guard who was killed in the crossfire, despite the East German border guards shooting at him — hitting their target 17 times, including in his lungs — Tews didn’t stop until he made it to the other side. The Western side of the Berlin Wall. He made it, albeit badly wounded, but he made it.

Democracy

Democracy.

This is a relatively new word for much of Germany, about 25 years. For millennials like myself, this can be difficult to comprehend, having been born into a world of free will and choice.

While I (hopefully) will always be part of this world of personal liberties, I believe it’s important to understand the policies of the past and the hardships of the people, in order to have an educated view of the world.

On a recent trip to Germany, journeying through Leipzig and Berlin, I had a chance to explore this. At the best possible time, too: the 25th anniversary of Peaceful Revolution in Leipzig and the fall of the Berlin Wall. The energy was palpable, the museums abuzz, and the cities full of commemorations and festivals.

Now, I’d like you to join me on a journey — both physically and emotionally — through Germany, exploring its Berlin Wall history and unified present.

A Glimpse Into Germany’s Tumultuous History

It wasn’t until 1989 with the taking down of the Berlin Wall and the country’s re-unification in 1990 that Germany as a whole began to experience a true democracy. I begin learning about this — actually the time leading up to this — at the Forum of Contemporary History Leipzig (Zeitgeschichtliches Forum Leipzig). My guide for a tour of the space is Sebastian, who takes me through the permanent exhibition on the change in politics in culture in Germany before and until reunification.

On October 9, 1929, a special peaceful demonstration of 70,000 angry citizens took place in an attempt to have the Berlin Wall taken down, a divide that had caused people despair for 28 years. The risk these people took was immerse, with 8,000 armed Stasi police — the apathetic people who had spent their time reading everyone’s mail, arresting innocent citizens and throwing them into unsanitary jails for torture and interrogation, and keeping East German citizens from seeing their loved ones on the other side.

In the end, amazingly, no shooting took place. And soon after, the people got their wish, as the Socialist Unity Party — the main political party in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) — was at this point trying to save itself. It was this event that spearheaded a series of events that would lead to the fall of the Wall and true Democracy in Germany.

The Creation Of The Berlin Wall

Despite having been allies during WWII, the Western Allies and Russia quickly became divided after the fighting ended. While the US, Britain and France wanted to create a democratic Germany in their occupied zones, the Soviet Union wanted a Socialist Party in their zone in the East. Soon, Eastern Germany was being governed under the Socialist Unity Party (SED), whose goal was keep Capitalism out of the country.

The Berlin Wall was built on August 13, 1961, created in an effort to keep citizens of Eastern Germany — then called German Democratic Republic (GRD), with “Democracy” only in the name — from fleeing to the more liberal West. In almost an instant, relationships were destroyed and liberties were stolen.

Take for example a woman named Helga Aue, separated from her husband, Wolfgang, who, unlike her, was not a Communist. He ran to the West while she stayed in the East with their two children. Until the Wall fell and they were able to reunite, they were only able to spend short vacations and public holidays together.

But even this was risky, as any East German seen associating with a West German — even if it was so much as wave — risked being arrested and interrogated by the relentless Stasi police. These public servants watched everyone and everything, and if you made the wrong move you could find yourself in horrendous conditions, never speaking to your family again.

Lives were also taken, literally, as anyone trying to cross the border could be shot. It didn’t take long for the Wall to come to symbolize inhumanity, oppression and death.

There are over 600 deaths associated with the Berlin Wall, and even more known casualties. Each year, these numbers go up as researchers learn more.

As I walk with Sebastian through 3,200 exhibits — ranging from text to photos to authentic video clips to artifacts — I’m taken into a world that’s hard for me to comprehend. There are life-sized displays and replica spaces of GDR living rooms from the 1970s and West Berlin refugee camps that I walk through that help to bring history to life. Yet still, with every word I read, every act of propaganda and oppression, I can barely comprehend it.

Walls hold videos of people desperately trying to climb through barbed wire and jump out widows to escape GDR, as well as propaganda posters showing young, healthy people who left and died of starvation in the West, which was rarely the case. A film plays with joyous music, showing the Communists and Socialists coming together in union for a better government in GDR, which was far from the truth.

My spirits lift toward the end of the exhibit when I see clips of excited East Berliners jumping up and down in excitement, tears of happiness streaming down their face as they legally cross into West Berlin for the first time in 28 years, finally able to see the friends and family they’d been separated from.

Artist Stories From The GDR

Next we learn about another viewpoint of the GDR, one that shows how the hardships of the society helped form strong bonds between people going through the same ordeal.

Not only is the Leipzig Spinnerai Galleries enlightening, but it’s one of the unusual things to do in Germany.

Once a cotton factory from 1907 and turned into an arts complex in 1992, the diaries of the workers during GDR times can be read, with the overall story being that the factory was a source of pride and provided a second family for the people, as they were all going through the same thing.

“It’s amazing how much history there is behind these walls,” says my guide, Laura. “I find it sad we don’t have any machines to show visitors, but they were all sold and destroyed.”

They do, however, have a room full of old black and white images of workers manufacturing the cotton and how the machinery and tools would have worked, as well as artifacts that tell the complex’ past. The factory history is s tangible, with the exposed red brick exterior and production train tracks, as well as a slight must of old concrete and brick in the air.

In terms of the spaces, there’s still an East Germany spirit of neighbors helping neighbors, a strong camaraderie dedicated to growing Leipzig’s arts scene. For some of the 120+ artists working onsite their foray into the professional art world is relatively new; however, for others it goes back to the times of the Berlin Wall.

Onsite is Leipzig’s oldest art gallery, Eigen + Art.

It’s been in operation since 1983, although as during the time of the GDR only approved art pieces could be showcased they were part of an underground scene. Gallerist Gerd Harry (Judy) Lupka used an abandoned house and backyard to showcase the illegal pieces and bring people together for discussion and idea exchange in a salon-style fashion. Interestingly, some of the artists shown during this period still showcase in the gallery today.

Another artist I have the pleasure of meeting is Sadia Sadia, whose latest installation, “Fugue (Die Wende)” is a tribute to her mother, who escaped the GDR on her third attempt and was almost killed in the process.

“My mother made a lot of choices I don’t quite understand,” explains the artist. “This is my attempt to connect with her and to better understand.”

The idea is simple albeit challenging, using two windows in the artist’s studio during daylight hours to show an individual “Everyman” blocking out the window panels one-by-one. The conclusion is a single window-lit pane of glass remaining, until it too is blacked out and there is nothing but darkness. Here, The Wall has been built.

One could easily spend an entire day exploring the free-to-enter artist studios and galleries to hear more stories like these, as well as other accounts and viewpoints of German culture. For me, however, time is of the essence, and I need to continue my exploration.

A Festival Of Lights

As stated above, today is the 25th anniversary of Leipzig’s Peaceful Revolution, and tonight the city is celebrating with the Festival of Lights. While it’s an annual celebration (so you may want to mark your calendar for next year!), this year’s is one of the largest, with 50,000 people attending to see the 15 different art, light and sound installations relevant to the event.

As I walk the sobering ringed road, I’m stunned at how relaxed it is — a testament to the peacefulness of the city. There is no screaming and chanting; instead, locals walk cobbled streets holding candles and banners, stopping to see written memories from 1989 projected on buildings, hear alternative music that was once banned playing proud, and watch illuminated water falls “flowing” down church exteriors to represent life.

It’s interesting to note that while West Germany celebrates the road to reunification on October 9 — the date of the Peaceful Revolution — East Germany celebrates on November 9 to coordinate with the fall of the Berlin Wall. This just shows the different ideologies of the people during that time.

Onward To Berlin And It’s Famous Wall

The next day, I head to Berlin to better gain a better understanding of this. First stop: The Berlin Wall. For anyone looking to seek understanding of Germany’s tumultuous past, this should be your #1 stop, as it symbolizes the oppression Germans in the GDR felt under the Socialist Unity Party.

Remnants of the Wall can be found all over the city, from symbolic public art to the Tear Garden connecting East and West Berlin to memorials dedicated to those who lost their lives trying to cross. Possibly the most notable reminder is the Wall itself, or at least what’s left of it. Located on Bernauer Straße — where the Berlin Wall had a particularly extreme effect, with apartment buildings forming the boundary between East and West, displacing over 2,000 people — sections of its remains have been turned into a memorial and museum. Opportunities for remembrance and reflection abound, with an outdoor memorial featuring enormous original photographs, a Documentation Center, National Monument, Chapel of Reconciliation and exhibits.

My guide at the memorial is a woman named Hannah, who walks me through a section of the site, which is 1.4 kilometers (0.9 miles) long in total. Standing on the once GDR side of the Wall in “No Man’s Land,” the area between the East and West walls where people who tried to cross were shot, I’m surrounded by steel bars marking where the divide once sat, along with crumbling graffiti-clad sections of the original divide.

One of the most humbling sections of the memorial for me is the Window of Remembrance, displaying photos and stories of those who died trying to cross the Berlin Wall, mainly young men.

Says Hannah, “This installation is important as it makes the commemoration individual and gives young people a way to approach the topic of the Berlin Wall. Sometimes it’s very abstract to those who didn’t live through that time, and this helps address that.”

The most difficult to digest is the story of a baby boy crossing secretly with his family. When the baby started to cry, the mother pressed her hand over the baby’s mouth, not realizing he had bronchitis and couldn’t breath through his nose. Both parents survived and succeeded in reaching the West; however, the infant was accidentally suffocated and died.

Another interesting aspect was the Incident Markers, which mark exact spots on the street where certain events happened. Each marker is dated with a code that you can correspond to a story on the Berlin Wall Memorial’s mobile-friendly website to learn what happened. For instance, Marker 38 showed the spot where an East Germany soldier went AWOL in 1962. I stood on the very spot.

Going Inside Of A Real Stasi Prison

After hearing about the Berlin Wall and the control of the Stasi, I wanted to know more about what exactly went on behind the scenes with the East Germany’s secret police. The once-working Stasi Prison in Berlin, also known as the Berlin-Hohenschonhausen), allowed for this.

My guide for the afternoon is named Andre, and he starts off in a courtyard, standing over a 3-D model of the prison. Interestingly, there weren’t always Stasi in the GDR. First it was a Soviet internment camp created after WWII, before becoming a prison, also used by the Soviets from 1947 to 1951. After that, SED took it over and employed their newly-created Stasi enforcement. In total, there were 17 Stasi prisons in Germany.

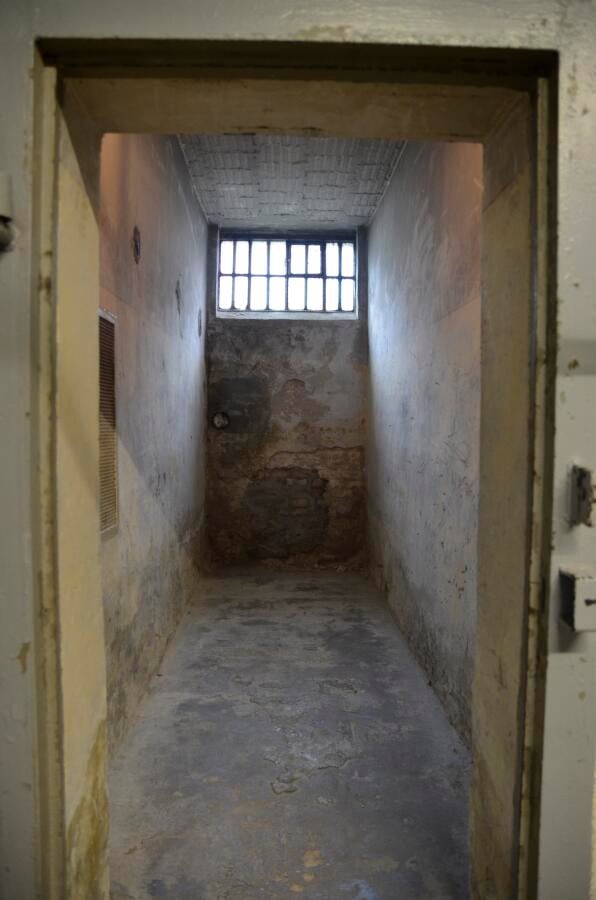

After an introductory talk I’m led into the prison itself to view the horrendous conditions endured by prisoners, many of whom were innocent of their accused crimes. I walk into cells so small my hands clam up from claustrophobia. These would hold small cells of 10 prisoners with no heat, ventilation or windows — just a single light bulb that burned 24 hours a day. A bucket was used as a makeshift toilet and was always full, leading to foul conditions, while the single bed in the room was only allowed to be used at night, with hands in sight and faces toward the door. As night was when the interrogations occurred, this was part of a master plan to deprive prisoners of sleep, and hopefully break them into confession.

Under the Soviets and Stalin, violence and brutality were also used. Because Stalin gave his police a quota to fill, innocent people were taken off the streets — with no rights to call loved ones or a lawyer — and thrown in prison to be tortured, often for many years.

Can you imagine living in fear that you or your husband/wife/mother/father/child could be captured and you might never be informed?

Additionally, many prisoners were sentenced to forced labor. Over the years it was active, more than 20,000 people arrived as “victims of communist tyranny,” many never even getting a trial. More than one thousands of these people died, buried in nearby bomb craters.

At the end of the 1950s a new prison was built, as the Stasi hoped to appear more humane in the eyes of the United Nations, not to mention Stalin had died on March 15, 1953. This allowed for an easier transition into less violent interrogation tactics. While physical brutality was forbidden, guards and interrogators now moved to more intense psychological torture. For instance, they would keep prisoners in solitary confinement or long periods of time with no contact with anyone, or they would keep their whereabouts a secret as to make them feel lost and helpless.

As the rooms allowed for sunlight to stream in but weren’t actually windows you could see out of, interrogation rooms were outfitted with beautiful nature views so that when a prisoner was brought in for questioning he would yearn for what he couldn’t have — unless, maybe, he confessed. The prisoners never really knew what their fate would be one way or another.

The complex was a secret from the public, with no average citizen allowed to enter its walls or know what actually went on behind them.

Meet any former prisoner today and you’ll know it was unspeakable, as many of them have psychological disorders and are still haunted by the past. Most the guides at the Stasi Prison today are former inmates, and can give you a firsthand account of what happened during that time, I’m guessing a cathartic experience to share their story with experiences.

As soon as we step into the newer prison, an older German gentleman in my tour group bursts, “This smells like GDR! That rubbery linoleum smell. I remember it.”

The outburst shows he lived in the GDR, and how recent and still vivid these events really are.

Stories Of GDR Prisoners

Throughout the prison-turned-museum I learn so many sad stories of prisoners that it was difficult to digest it all. In 1945 especially there were a number of upsetting arrests of innocents. For instance, a 23-year old insurance clerk Named Lottchen Fischer was wrongly accused of being aligned with the Nazis, arrested and tortured into a false confession. She went on to spend five years working in labor camps until she was freed. Famous actor Heinrich George was another, arrested for acting in an anti-Semitic film. During his time in prison and work camps he lost 83 pounds in about a year from malnourishment and died during an operation. In 1998, after he’d passed away, he was found innocent by Russian authorities. It was too late.

Then there was politician Helmut Kind, secretary of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), arrested and accused of “creating a civil party.” After doing prison time and being sent to a labor camp — even being forced to help build the atrocious cells that himself and other innocents were forced to live in — he was freed after four years when his labor camp dissolved, never receiving a trial or verdict.

And it wasn’t just East Germans who were captured and imprisoned. Anyone suspected of acting or thinking against the GDR government, whether living in the East or West, wasn’t safe. Take for instance West Berlin lawyer Walter Linse, kidnapped in 1952 and killed in Moscow, Russia, in 1953.

The last prisoners were released on December 9, 1989, a full month after the fall of the Wall, an important even these people were unaware had even happened.

Expression Through Art

And then we arrive at The East Side Gallery, a 1.3-kilometer (0.8-mile) long series of 101 murals done with a theme of liberty, peace and human rights. After hearing about all of the oppression and persecution, I suddenly fill with hope. What a beautiful place Germany has become with beautiful people. During the GDR painting and artwork on the East Side of the Berlin Wall was forbidden, although on the West Side colorful murals could always be found. Today, people can speak their mind without issue, showing their individuality and creative spirit in the process.

I feel inspired by the works I see before me, happy with the ending of the GDR story and glad it concluded with a re-unified Germany where people can have their own free will and ideas — even voicing them on a Wall that once symbolized oppression.

I also feel appreciative, especially when I see paintings of American flags as symbols of democracy and liberty. Born in 1987 in New York, I never had to know what it’s like to be separated from family and friends, to live in fear of being interrogated or captured for no reason, or to be told where I can and can’t go. No matter how much I learn, I truly can’t imagine.

But thanks to sites like the Berlin Wall Memorial, the Stasi Prison, Spinnerei and the Forum of Contemporary History Leipzig, I can try to better understand. Because with all the tragedy that we see on our television everyday, what’s more important than learning from the past and trying to understand? Understand each other. Understand other beliefs and cultures. Understand basic human rights. Understand how to stop history from repeating itself.

Understand that everyday citizens have the power to make big changes for the better, and they don’t need to stand for global injustice.

Never forget what happened. Never take for granted your freedom. Never stop learning about the past so that people can have a better future.

Recommended Film

*The stories and information from this article were sourced from materials and docents from the sites mentioned in the article. These include The Berlin Wall Memorial, the Forum of Contemporary History Leipzig, The Stasi Prison and Spinnerei.

Have you explored Berlin Wall history in Germany? Was was your experience like? Please share in the comments below.

My trip to Germany was sponsored by the Germany Tourism Board. I was not required to write this post nor was I compensated for it. All opinions are 100% my own.

Hi, I’m Jessie on a journey!

I'm a conscious solo traveler on a mission to take you beyond the guidebook to inspire you to live your best life through travel. Come join me!

Want to live your best life through travel?

Subscribe for FREE access to my library of fun blogging worksheets and learn how to get paid to travel more!

Turn Your Travel Blog Into A Profitable Business

Subscribe to my email list to snag instant access to my library of workbooks, checklists, tutorials and other resources to help you earn more money -- and have more fun -- blogging. Oh, and it's totally FREE! :) // Privacy Policy.